Scientists obsess over measurements. They are the bedrock of modern scientific investigation, and often buttress decision-making and policymaking at the highest levels of our government. Gross Domestic Product, life expectancy, and educational achievement are classic examples of keystone governmental measurements.

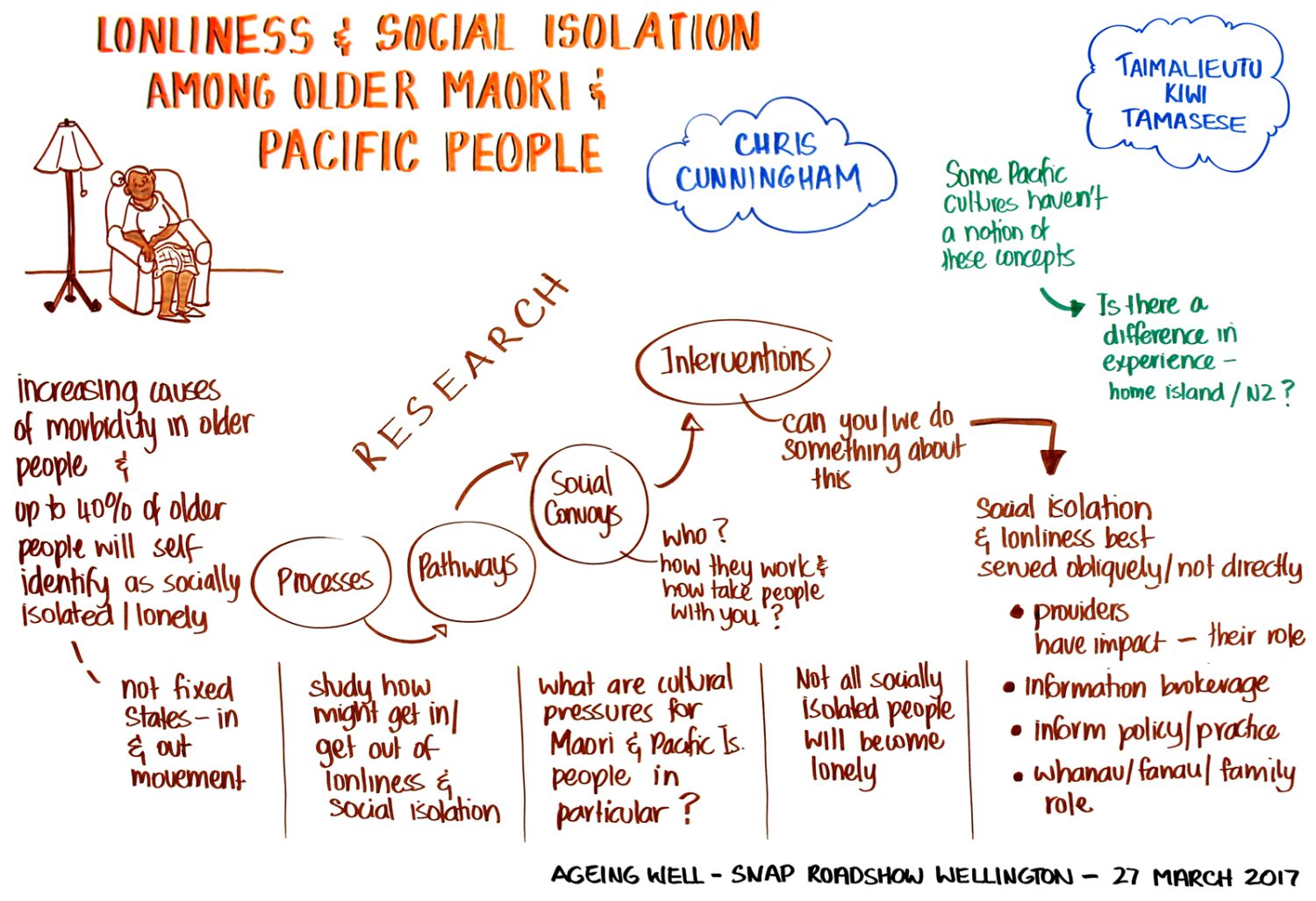

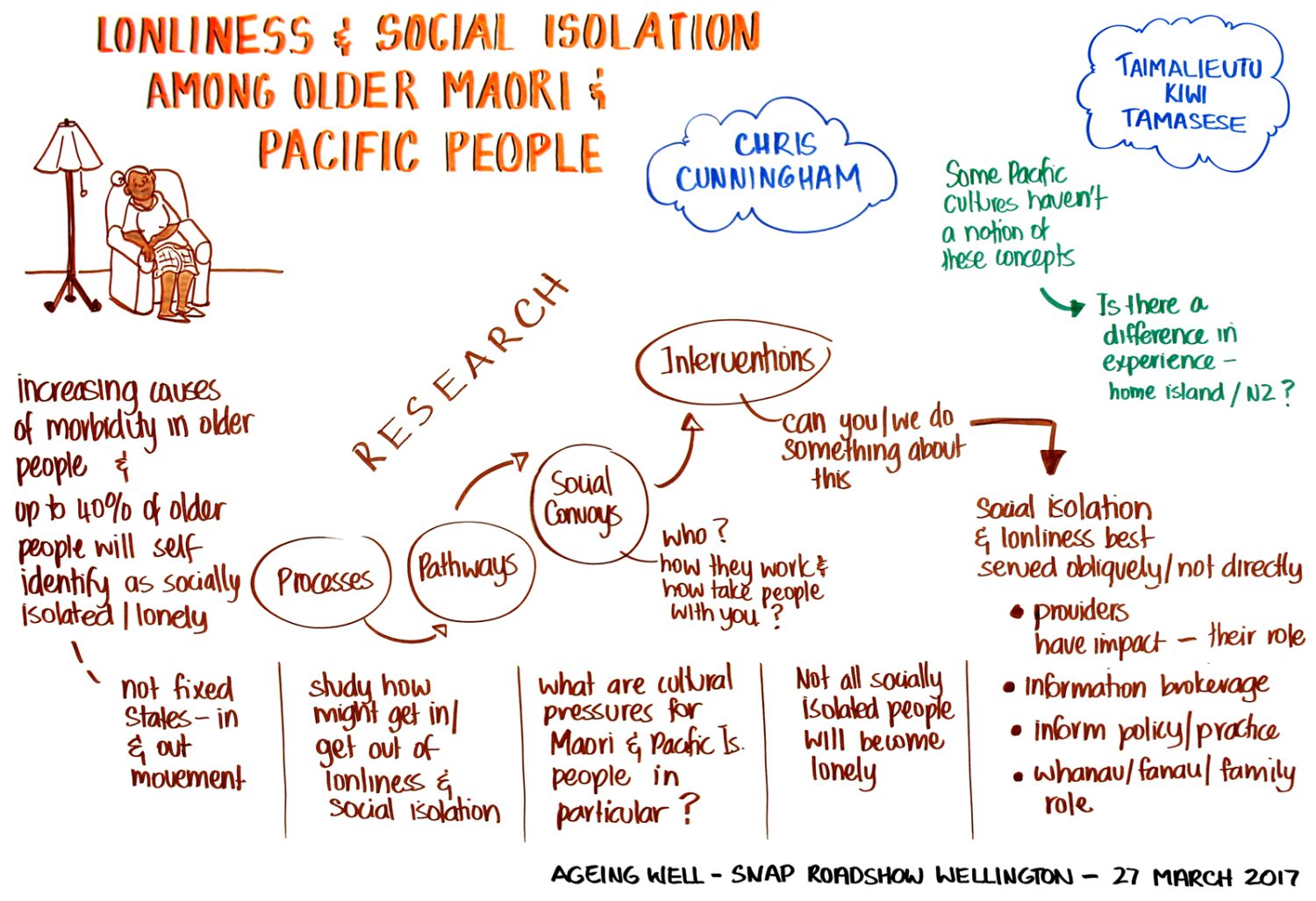

But what happens when the way scientists have measured something, such as loneliness, appears to be imprecise or inadequate? Such was the situation Ageing Well Principal Investigators Charles Waldegrave, Professor Chris Cunningham, and Taimalieutu Kiwi Tamasese found themselves in when they began to explore loneliness in older Māori and Pacific Peoples. Waldegrave, the coordinator at the Family Centre Social Policy Research Unit (FCSPRU), an independent research agency located in Lower Hutt, Wellington, wanted to develop an ‘early detection system’ for signs of loneliness and social isolation among these groups.

However, Waldegrave’s team began to survey older Māori and Pacific peoples about loneliness, they discovered some participants who they suspected were lonely were not showing as such on a prominent international scale.

The scale in question is called the De Jong Gierveld Total Loneliness Measure. Developed in the Netherlands, it is widely employed both in Aotearoa New Zealand and internationally. It is highly regarded as a reliable and accurate tool. And when it comes to “universal aspects” of loneliness, Waldegrave clarifies, it captures these exceedingly well. Yet, as the research team discovered, some culturally specific aspects of loneliness were being missed.

No measurement of loneliness will ever be one hundred per cent accurate. Everyone, after all, experiences feelings of loneliness differently. And loneliness is slippery. It is intangible – it is difficult to pin down and measure accurately. It is a state of mind and perception. But in a multicultural society, allowance should be made for cultural differences.

Other research undertaken by Ageing Well demonstrated that certain ethnic groups are more susceptible to loneliness (see the work by Drs Keeling and Jamieson). It follows that certain groups may experience loneliness in ways not anticipated by the predominantly Western loneliness scales used in New Zealand.

Social connections for older people are very important for their health and quality of life and we have a responsibility to correct western bias... and studies have shown that the effects of loneliness and social isolation “lead to greater ill-health and earlier death.”

About the research

The research team concluded that culturally specific aspects of Māori and Pacific loneliness are not being captured on standard, international measurement scales, and this may have dramatic ramifications for policymakers. “Our perspectives need to be challenged,” argues Waldegrave, “as western scales are not adequate measures of loneliness and social isolation for kin and spirituality-based cultures.”

To rectify this failure to account for cultural aspects of loneliness, the research team set about designing – with older Māori and Pacific peoples – co-created scales that took into account those culturally-specific factors affecting them. The co-created questions were designed to identify the specific cultural aspects of loneliness which brought the cultural nuances into sharp relief. One participant noted: “we don’t focus so much on individual personal feelings like your sort of cultures. We are moved by collective experiences within our whānau and cultural communities.”

The co-created questions focused on loneliness experiences related to the changing roles of older people in contemporary life, their extended family responsibilities, spirituality, and the impact of contemporary living on their cultures.

In the Māori study, 196 participants – 50 to 80+ years – completed the different loneliness questionnaires. The researchers then compared the results. A considerable number of participants did not register as particularly lonely on the De Jong Gierveld scale, whereas they did register as lonely on the responses to the co-created questions which focused on the culturally specific aspects of loneliness that they might experience.

“The differences between the scales were statistically significant”, Waldegrave explains. The new co-created loneliness scales offered a different picture of how lonely older Māori and Pacific peoples are from western ones commonly in use. Older Māori and Pacific peoples are more lonely in different areas.

The study also identified what factors made these groups more or less likely to be susceptible to loneliness and social isolation. Depression, abuse and discrimination ranked highly as factors likely to increase the risk of loneliness and social isolation amongst participants, the study found. “Negative life course events” also raised the odds. A bounty of factors reduced the risk: secure housing, good health, higher wellbeing scores, faith and religion, social networks and connection, good material standards of living, and safe and friendly neighbourhoods.

These new insights will allow researchers to chart a path forward to minimise the impact of cultural loneliness for Māori and Pacific peoples.

The research team have also received an additional grant from Ageing Well to develop a Kaumātua Future-Proofing Tool, which will provide an evidence-based checklist for those designing ‘culturally rich’ services for the burgeoning, ageing Māori population.

Early detection of “common pathways” leading to loneliness or social isolation permits the team to develop ways of encouraging connectedness and enduring relationships during older age. As a result, Waldegrave envisages “better-targeted services and policies” to improve the quality of life of older Māori and Pacific people, and increased “cost-effectiveness” of services.

Social connections for older people are very important for their health and quality of life and we have a responsibility to correct western bias, Waldegrave explains. Numerous studies have shown that the effects of loneliness and social isolation “lead to greater ill-health and earlier death.”

The ramifications of the study’s discoveries are significant: one of the dominant measures of loneliness used in New Zealand, based on western concepts, fails to capture culture-specific aspects of Māori and Pacific loneliness. Failure to capture these aspects of loneliness creates the problematic misunderstanding that key areas of older Māori and Pacific peoples’ experience of loneliness are not taken into account. It masks a problem that key decision-makers do not know exists.

As Waldegrave explains, “We have very few Māori measurement scales, and so our standard measures may be only capturing universal aspects of indices and not the Māori-specific aspects. This may help explain the persistent gap between Māori and non-Māori wellbeing outcomes.”

This problem regarding the cultural components of loneliness has bigger implications still. It means that the raw data that policymakers, statisticians and ministries are using—the data they use to make critical funding decisions—are “blunt and imprecise” says Waldegrave.

That disadvantages older Māori and Pacific peoples, as service planning for their communities, will only be effective if the decision-makers have accurate data. Understandably, there was significant interest in these findings from Māori and Pacific stakeholders, end-users, and other funding agencies. Māori and Pacific groups have reached out to the FCSPRU team to work on developing programmes to incorporate these findings. Aspects of this research were also presented by Charles Waldegrave at the Gerontology Society of America 2020 Annual Scientific Meeting, the largest and most prestigious international conference on ageing, where it received the Ollie Randall Symposium Award.

Conclusion

The research team have also received an Emerging Opportunities Research Grant from Ageing Well National Science Challenge to expand the study further to explore the health and service needs of Māori. Collaborating with Dr Catherine Love (Te Atiawa, Taranaki, Ngati Ruanui, Nga Ruahinerangi), also of the Family Centre, and Professor Chris Cunningham (Ngāti Toa, Ngāti Raukawa), the team hope to develop a Kaumātua Future-Proofing Tool, which will provide an evidence-based checklist for people, organisations, and ministries designing ‘culturally rich’ services for the burgeoning, ageing Māori population.

The lessons of this study transcend its focus on loneliness and social isolation. Future research on older Māori and Pacific peoples needs to be receptive to their unique cultures, languages, and frames of reference. Using measurement scales that take into account the cultural aspects of Māori and Pacific peoples’ health and wellbeing may allow New Zealand to better bridge the inequity gaps in health outcomes so that these older groups can age well.